You know those events you wander into with no real expectations – and then halfway through you realise, quietly, this is special? Kristina Kallas’s lecture at RMIT University was one of those rare moments. Let me tell you what she spoke about, you might want to lean in too.

When Estonia’s Minister of Education and Research, Dr Kristina Kallas, stepped up to the lectern at RMIT in Melbourne, 27 November 2025, she did not just present policy or sound like “just another politician on script”. She spoke with the kind of clarity, urgency and care that made a Council Chamber lean in.

She spoke as a lifelong educator, policymaker and citizen of a small country that has decided to treat artificial intelligence (AI) not as a threat to be feared, but as a challenge to grow into.

By the end of the lecture, “Redefining Education: Harnessing AI for Cognitive Growth”, the audience had been taken on a journey from 17th-century Estonian village schools to a national “AI Leap” program that will put a tailored version of ChatGPT and Gemini into the hands of every Estonian secondary school student from January 2026.

Kristina Kallas earned a loud, sustained applause that is not standard issue in academic halls.

The Minister began by situating Estonia: a Nordic-Baltic country of just over one million people, 171,000 students and around 500 schools – some with only a handful of children, especially on small islands.

Despite its size, Estonia is widely recognised as one of the most digitalised countries in the world: 100% of public services are online, from tax returns and voting to driver’s licences and, as of 2025, even filing for divorce.

This digital infrastructure is not separate from education – it shapes it. To function in a fully digital state, young people must learn to live and act in that environment. Schools therefore cannot sit outside the digital ecosystem; they are part of it.

But Estonia’s education story did not begin with e-government. Kallas reminded the audience that the education system is older than the Estonian state itself. Under Swedish rule in the 17th century, a network of schools and a university were established on what is now Estonian territory. Compulsory schooling followed in the 19th century, and by 1881 literacy had reached around 94% – among the highest in Europe at the time, despite Estonia being a poor, rural region.

Crucially, when the Republic of Estonia was founded in 1918, many of its leaders were not lawyers or businessmen, but teachers, headmasters, journalists and writers. In Kallas’s words, Estonia is in many ways “a nation founded by education leaders”.

That tradition was tested during the 50 years of Soviet occupation that followed 1940. Estonia maintained its historic school structure, but a parallel Russian-language system was created, under Moscow’s jurisdiction. Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonia has worked to integrate those schools into a single national system. The final step – shifting Russian-medium schools to Estonian-medium instruction over a nine-year transition – is now underway, accelerated by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

In the 1990s, Estonia faced an urgent question: what should a modern Estonian curriculum look like? The answer was to look across the Baltic Sea to Finland, then – and still – one of the world’s strongest education systems. Estonia adapted the Finnish model, but also added something bold for its time.

In 1997, Estonia launched a major initiative to bring computers into classrooms and connect all schools to the Internet. This was met with the now-familiar worries: computers would make students “lazy”, no one would memorise facts any more, children would just play games and use Wikipedia. Sound familiar?

Despite the resistance, the program went ahead – and helped shape an entire generation of Estonian tech leaders. Many of the founders behind Skype, Wise (formerly TransferWise), Bolt and other Estonian unicorns are alumni of this early “digital leap” in schools.

This positive experience matters today. Because Estonia has already lived through one wave of technological anxiety and seen the long-term benefits, its attitude to AI is more pragmatic and hopeful than purely defensive.

Where some systems instinctively push AI away, Estonia is asking: how do we bring it in – wisely?

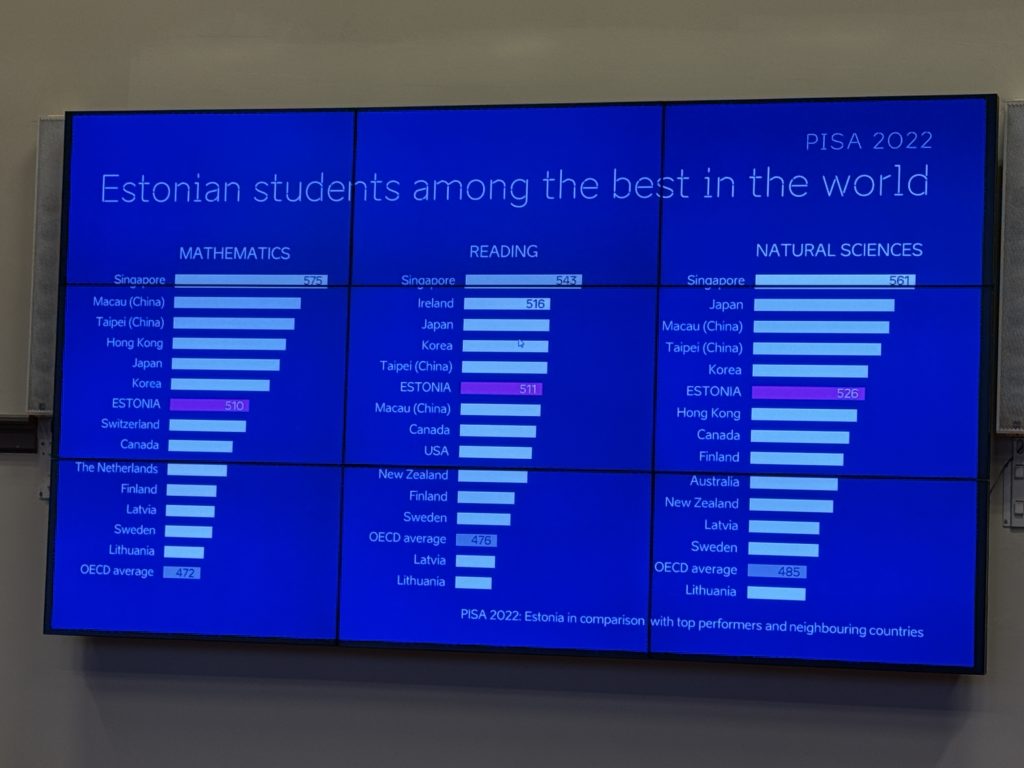

Before turning to AI, Kallas outlined the foundations of Estonia’s strong performance in international assessments such as PISA, where Estonia ranks among the top countries globally and first in Europe.

Key elements are described here.

High expectations and hard work

The national curriculum is demanding. It assumes that students, teachers and parents all contribute. There is homework. There is debate about pressure. But there is also a deeply rooted cultural belief that education is an investment into human capacity and that each generation can improve its life chances through learning.

Teacher autonomy

While Estonia has national learning standards (what students should know), teachers have high professional autonomy in how they teach. They can decide whether to use digital devices or not, when to take learning outside the classroom, and which methods suit their students.

Kristina Kallas was clear:

If we over-prescribe teachers’ actions, we turn them into clerks rather than professionals. Autonomy, she argued, is fundamental to serving diverse children in real classrooms.

Equity and diversity

Estonian children go through nine years of comprehensive basic education together, without selective “smart” streams. The goal is that by age 16 they should all be able to reach strong levels in key subjects, regardless of their starting point. The school network itself is diverse – from large urban schools to tiny rural ones and community-driven private schools – and parents can choose environments that fit their children.

Early childhood education

Perhaps the most important element, in the Minister’s view, is what happens between ages 1 and 7. Early childhood education is widely accessible, tax-funded and guided by a national curriculum. It focuses not on early reading or maths, but on social-emotional development and self-regulation – giving children a more equal start, regardless of home background.

Estonian children start compulsory schooling at age 7, meaning by age 15 they have spent fewer years in formal school than peers in countries like Australia – yet they still perform extremely well. Kallas sees this as strong evidence for the value of high-quality early childhood education.

Growth mindset and creativity

In PISA surveys, more than 80% of Estonian students report believing that intelligence can be developed, not something you are simply born with. Estonia also scores highly in creative thinking and problem solving. This culture of “you can get better if you work at it” is now central to how Estonia is approaching AI.

Kallas did not minimise the scale of the challenge AI poses. When a device in a student’s pocket can perform in seconds what schools may take years to develop, the risk is not abstract.

Estonia’s biggest fear is that, without a deliberate strategy, students will use AI for “heavy cognitive offloading” – outsourcing so much thinking to the machine that the AI learns, but the child does not.

To explain why this matters, Kallas turned to basic neuroscience. Human brains, she reminded us, tend to operate in two modes:

Lower-order cognitive processes – memorisation and repetition. Once we learn to ride a bike or remember that the Second World War began in 1939, we store that information and reuse it without much effort.

Higher-order cognitive processes – analysing, evaluating, creating; re-organising knowledge for new situations. These processes are energy-intensive, and anyone who has studied for an exam or learned a completely new task in a day knows the exhaustion that comes with it.

For the last 200 years, most education systems have focused on the lower part of Bloom’s taxonomy: remembering, understanding and applying knowledge. AI now forces a pivot upwards. Computers – and especially AI – already outperform many humans in lower-order skills.

If humans are to remain “sovereign thinkers”, we must consciously train far more people to live much more of their day in higher-order thinking.

This is not about asking everyone to use AI “more”. It is about using AI differently – to free up human energy for deeper reasoning, systematic thinking and creativity, rather than replacing those capacities.

Out of this reflection came Estonia’s AI Leap (AIA) program, a national experiment in higher-order thinking.

In early 2024, the Ministry of Education convened an AI Council bringing together developmental psychologists, neuroscientists, brain researchers and education specialists. Their task was to design a strategy that uses AI to strengthen higher-order cognitive skills in schools, not weaken them.

The result is an ambitious, system-wide initiative:

AI Leap Foundation

A public–private foundation was created, funded 50% by the Ministry and 50% by private donations, largely from the tech sector.

Partnerships with OpenAI and Google

Estonia negotiated a special licence for a customised version of ChatGPT (from OpenAI) and Gemini (from Google). This “Socratic version” is designed not to simply hand over answers, but to respond with questions, prompts and counter-arguments that force students into an ongoing dialogue – mirroring the Socratic method.

Whole-system rollout

Around 30,000 secondary school students and 5,000 teachers will be covered. Teacher training began in August 2025; from January 2026 all secondary students will receive individual licences to use these tools in every subject, from mathematics to music and art.

Teachers at the centre

Kallas was explicit: the key variable is not which AI version students use at home – a generic app on their phone will always be a click away – but how teachers redesign learning processes in the classroom. If teaching stays the same, students will simply ask AI to write their essays and do their assignments. If teaching changes, AI can become a scaffold for deeper engagement.

Scientific monitoring and new exams

Two research teams – one in neuroscience, one in education – will monitor the program from January 2026. They will study how students actually interact with AI, what learning strategies they use, and how motivation and deep learning are affected.

In parallel, new national exams are being developed for 2027 to explicitly assess analytical, systematic and higher-order thinking, alongside traditional subject knowledge. Estonia wants evidence that the AI Leap is genuinely shifting cognition, not just rhetoric.

Kristina Kallas did not pretend that every risk has been solved. She noted concerns about cultural and linguistic bias in AI models trained largely on English-language, North American content, and about students choosing to interact in English rather than Estonian. These issues are part of the ongoing research agenda.

Throughout the lecture, the Minister’s enthusiasm for the topic and for her country’s way forward was palpable.

She did not claim Estonia had all the answers. Instead, she extended an invitation: “We invite the world to lean in with us and to learn with us, to be more risk-taking in applying AI in education.”

The message was simple.

- AI will not wait for education systems to feel ready.

- Simply banning or ignoring it will not protect students from cognitive offloading.

- The real task is to re-design learning so that AI supports, rather than replaces, human thinking.

For a small country founded by education leaders, that evolutionary leap feels like a natural, if ambitious, next step.

If you have the chance to hear Kristina Kallas speak in person in the future, consider it strongly. This is not a minister reading from a script; it is an educator-in-chief thinking aloud with her audience.

Many of us left the room quietly proud to be Estonian, to be connected to Estonia – and curious to see what the AI Leap will reveal by 2027 and beyond.

See photos from the Minister’s visit on Flickr.com and read about Estonia’s AI Leap program here.